Project Spotlight: Embassy Bank

Client Name: Embassy Bank Project Name: Embassy Bank at Liberty Street Construction Completion/Opening Date: August 2021 Design Team: Silvia Hoffman,…

Read More >It’s time for another installment of Chris’ History Corner. Enjoy!

Chris Worton, RA is MKSD’s resident architectural history guru and during the pandemic when we were all working exclusively at home, he began writing a daily feature for the staff on our Teams page. He impressed us all with his vast knowledge and enthusiasm and we looked forward to reading each new installment.

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, SOM (Gordon Bunshaft): Built for Yale University and completed in 1963, the Rare Book Library and Archive was designed by Gordon Bunshaft of Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill. Dedicated to rare manuscripts and rare books, it was financed by the Beinecke family and is one of the largest facilities in the United States, and the world, to hold such a collection.

At the time of the building and construction of the Beinecke Library, SOM was becoming, if not already, one of the best representatives and purveyors of modern architecture in the United States. Bunshaft joined SOM in 1937, one year previous to the company’s founding, and eventually rose up to partner, designing such iconic SOM buildings as the Lever House and the Manufacturer’s Hanover Trust Branch Bank, both in NYC, amongst other buildings. In 1988, Bunshaft was the recipient of the Pritzker Prize, the highest honor that can be bestowed upon an architect.

Like many iconic, Modernist buildings, this structure is riddled with references to classical architecture, in particular Greek and Roman Temples, and their siting. The Library sits within Yale University’s Hewitt Quadrangle. Buildings that comprise the quadrangle are the University’s dining facilities, main auditorium, and administrative offices; in essence, it is a modern-day forum on campus as it is a gathering place of great significance. In ancient times, the foras throughout the Roman Empire had, at the very least, a basilica (an indoor building that served as a court building and held other official and public offices) and a Temple of Jupiter at the north end. Here, at Yale, the Library is not a temple to religion, but a temple to knowledge. A temple and a library are not all that different from one another as they both store objects. Roman Temples stored precious objects (jewelry, sculpture, art, et cetera) as offerings to the gods and the state; the Beinecke Library stores precious objects (rare books and manuscripts) as offerings to the advancement of human knowledge.

Though the Library is a temple in a Roman Forum (i.e. the Quadrangle), the Library acts more as a Greek Temple. Roman Temples, unlike Greek Temples, were not objects in the round (i.e. free on all 4 sides), but rather embedded within the surrounding buildings of the forum. Because of this, only the front end and portions of the sides were visible. Therefore, Roman Temples were very frontal objects with a clear front, rear, and sides. Greek Temples, on the other hand, were floating objects in space and not meant to be experienced frontally per say, but intended to be approached from any of a number of angles. This is the case with Beinecke Library; it is not embedded in any adjacent buildings, but is free from them, allowing it to become an object within the space, not an object that is part of the space.

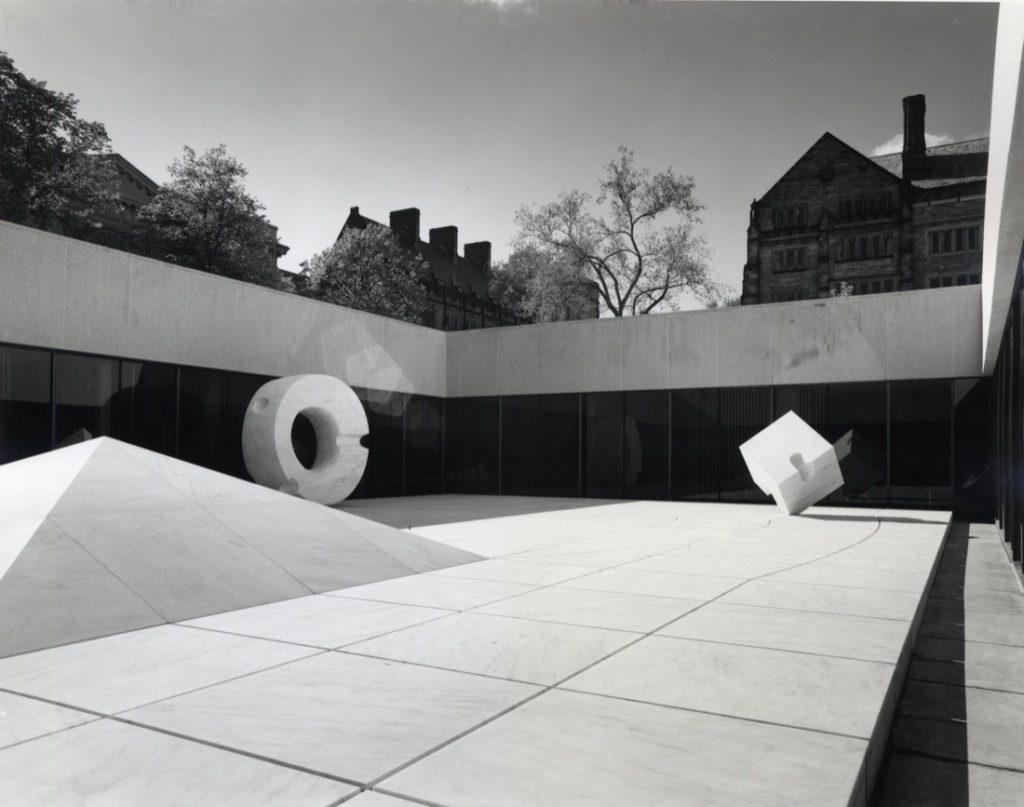

Approaching the Library from the main area of the Quadrangle, there are a number of classical references, both apparent and covert. First is the sunken court of the Library. Ancient temples, it should be recalled, always had an altar that was placed in front, and outside, of the temple. It was a raised platform in which the sacrifice of animals occurred. Here, at Beinecke, the sunken court is the altar. Whereas in ancient temples the altar was an object created by addition, here the altar is a void created by subtraction.

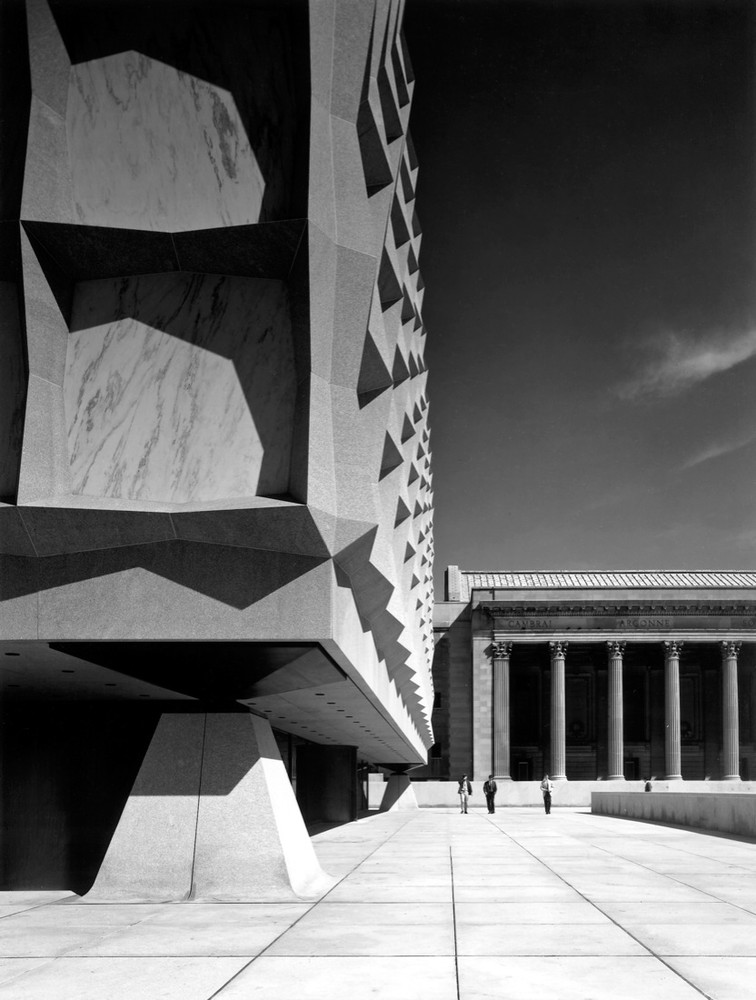

Further, we notice that the Library is separate from the earth; it is raised on (4) massive piers that lift the perimeter of the building into the air, creating a separation between that which is profane (the ground) from that which is sacred (the Library itself). Ancient temples also separated the temple from the profane ground by the raised platforms of the stereobate and the stylobate. Again, we have the same notion of raising this temple/ Library off of the ground, but the ancients placed it on an object created by addition whereas we moderns void out the object it is to be raised on by separating it from the profane ground.

Before studying the interior and plan, a few more observations on the exterior. The Library mass is comprised of translucent veined marble and granite panels in between a rigid and regular grid of opaque material. In this we have a modern interpretation of the temple again. The opaque verticals are the columns of the temple/Library and the translucent panels are the voids between the columns. Even though there is not a physical transparency between the verticals, there is a sort of visual transparency in a sense, as these panels, though they don’t allow direct views in and out, still allow light. As for the verticals/ columns, they are contextual within the quadrangle and its siting. When looking at the temple/Library with the neoclassical architecture of the surrounding quadrangle, the temple/ Library replicates the same rhythm in the verticals as the nearby colonnades. In effect, the verticals are a colonnade. But, when we look at the temple/ Library in relation to the tall and distant neo-Gothic buildings beyond the Quadrangle, the verticals seem to replicate the notion of their spires. It is the abstract nature of the verticals that allow them to take on different roles with different buildings.

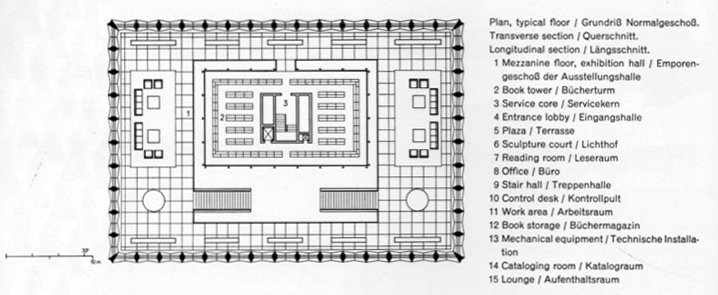

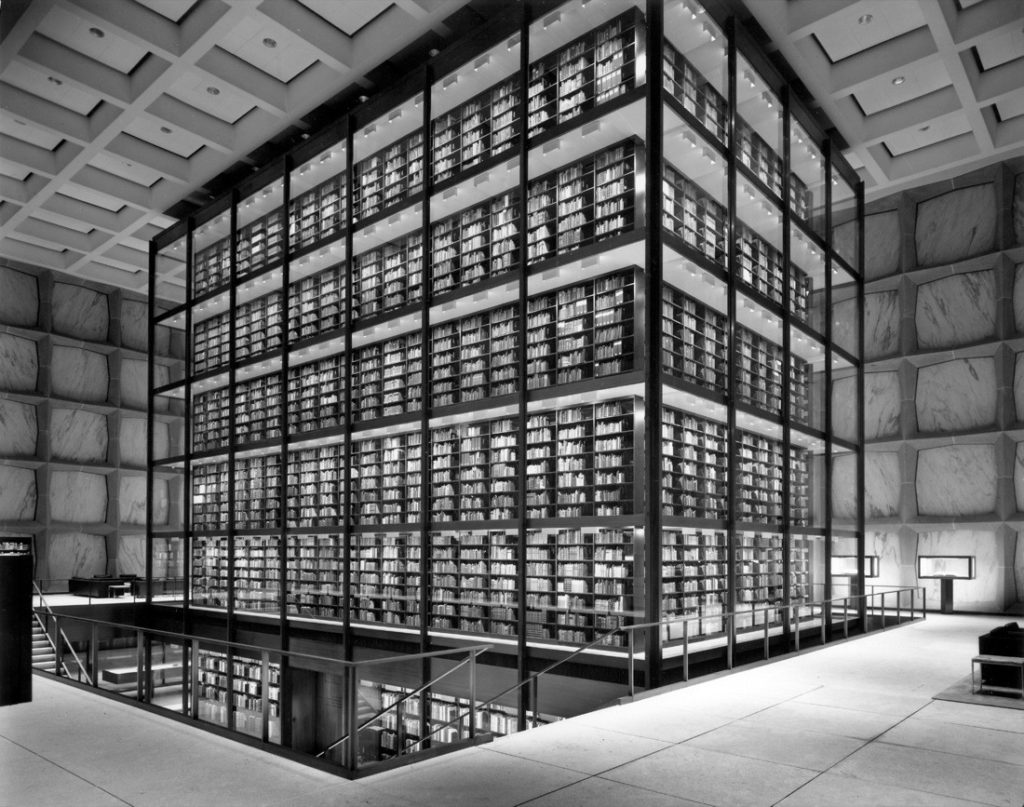

In plan, we understand more fully that the verticals operate as columns as they are represented in heavy poche and the translucent panels between are represented lightly . Further, when we look at the glass encased box of the rare books themselves, we begin to see this as the temple’s cella, the very interior room that was used to store the objects dedicated to the gods. But here, the cella is not a fully walled structure of marble but rather the opposite: a clean, transparent skyscraper embedded within the temple itself. Additionally, the cella is not a closed, inaccessible space for only the priestly class, but an open, transparent space for all classes to see and observe.

Looking up at the ceiling of the interior, it takes on the appearance of coffering, albeit in an abstract and less ornamental role than in ancient temples. Particular attention should be paid to the voids in relation to the perimeter grid as the grid of the ceiling aligns with the grid of the façade. So, on the interior we do not have (4) sides of a building plus a ceiling but rather (5) sides of a building, with the ceiling as the 5th elevation that has folded down in on itself.

In the end, the Beinecke Library unequivocally states: the ancient gods are dead and no longer determine the fate of humanity. Rather, it is knowledge that is the new religion and such a use of that knowledge now determines the fate of humanity.

Image Citation.

All Images from the website www.archdaily.com

Client Name: Embassy Bank Project Name: Embassy Bank at Liberty Street Construction Completion/Opening Date: August 2021 Design Team: Silvia Hoffman,…

Read More >MKSD architects, is happy to announce that Laura Clifton has joined our firm as an architectural designer and historic preservationist….

Read More >Written by Jessica Klocek, RA, LEED AP BC+D, Director of Healthcare Design at MKSD architects. We have all spent the…

Read More >